Communication into Language

We still need to go into far more detail about language beyond its origins, including discussions of:

• “objective reality” as shared among its denizens (whether or not they use language),

• each individual person’s subjective model of reality (likewise),

• areas beyond spatial reality, and

• more about the nature of form, meaning, and their association.

We are going to bother setting up some terms and a particular model of objective reality because it helps us to explain how and why people create particular types of language signals, which will be important in describing disorders in that conventional system.

Before proceeding, we would just like to quote United Air Lines:

For takeoff your seatbelt must be fastened low and tight across your lap. Insert the metal fitting into the buckle, and pull tight by pulling on the loose strap. To release, lift up on the faceplate of the buckle. It is important that you keep your seatbelt fastened at all times when seated to protect yourself from any unexpected turbulence. It’s going to be a bumpy night.

Okay, we admit it. That last line was Margo Channing (“All about Eve” screenplay, Joseph L. Mankiewicz).

Subjective Reality

Unlike objective reality, which we can just point to as a source of objects for examples (because it is precisely that: objective), we need to build up a model of subjective reality here so that we can usefully discuss its parts. When we are done describing this model, it will be easier to explain why we tackled the subjective part first.

The fundamental base of this section is derived heavily from Langacker’s explanations, although he might take exception to some of the exceptions that we have taken. Our terminology is different than in Langacker’s original descriptions, just because our terms have been easier for people to remember when they are not working with the model a lot. To be fair, we found it equally necessary to extend some of the terminology found in Mansfield (1997) to cover further models that had not been constructed there.

Ground (G)

We stated earlier that a communication event (and its circumstances) will establish an anchor point or “ground.” Mutual reliance on that ground tends to be such a stable assumption that participants (Ps) will use it readily to make joint references, such as when pointing at something with their finger (relative to their physical location), or identifying something with language. That stable expectation is reflected in P’s cognitive models of that anchor, where we will similarly identify that piece of the model as the ground (G).

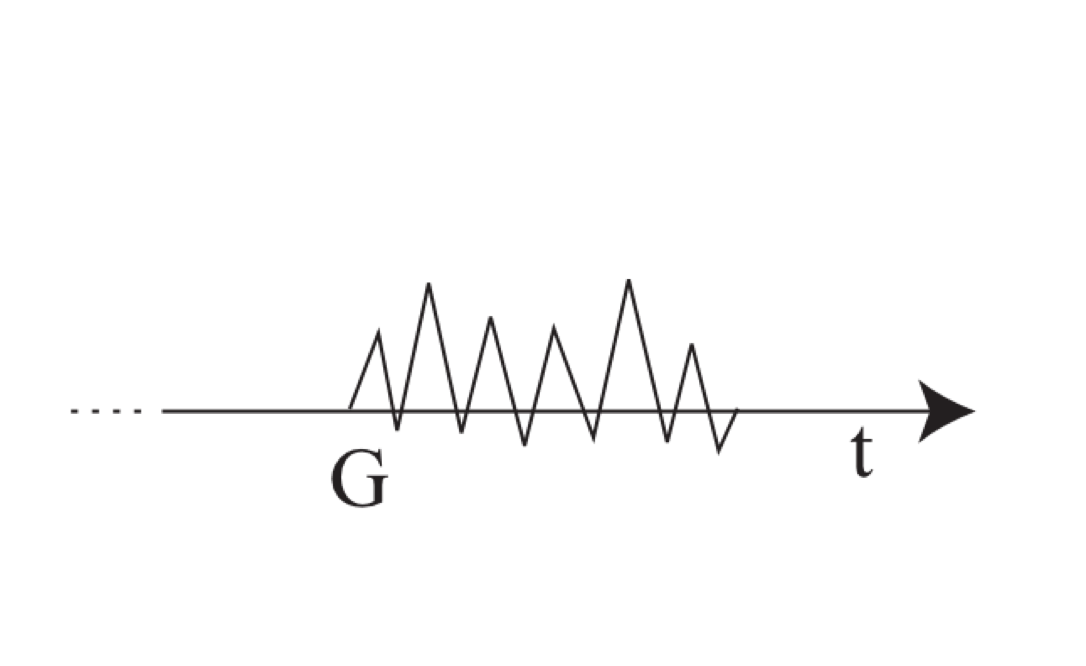

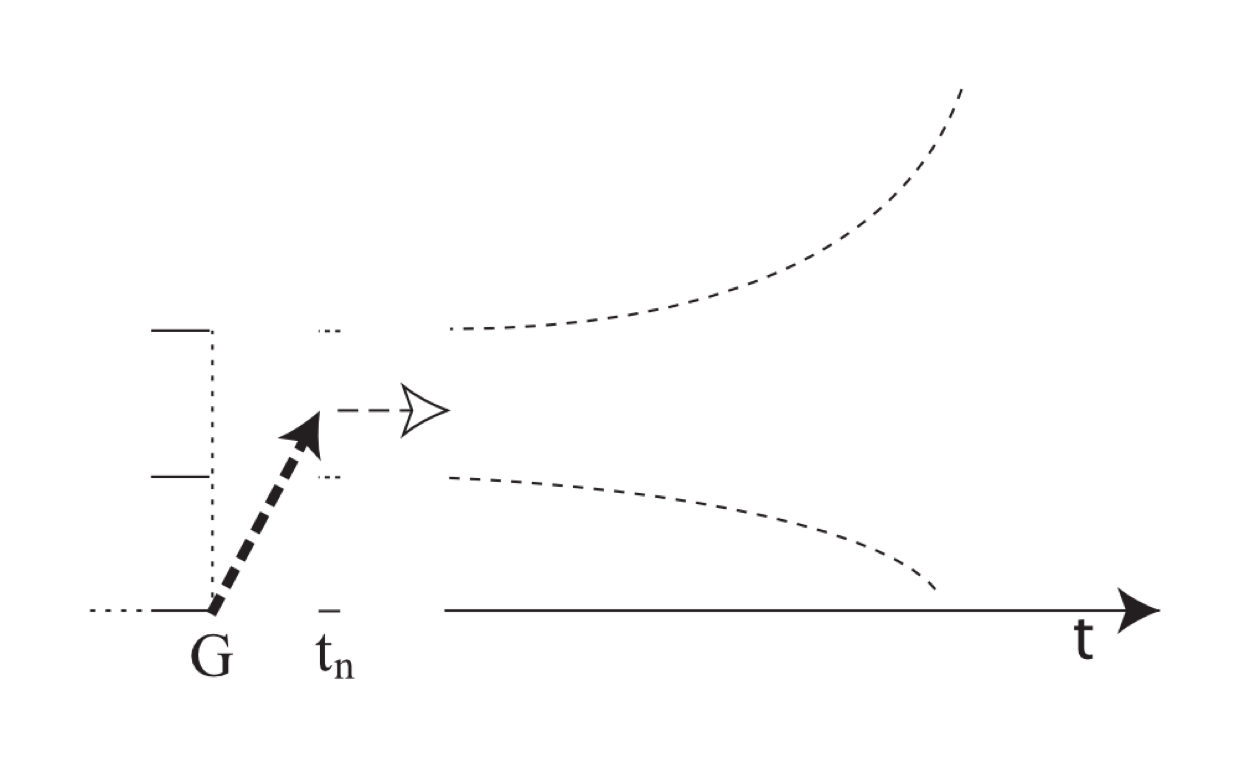

Now imagine G as associated with its specific moment in time (t), as opposed to portraying its embedding within the whole expanse of the timeline (which will come later):

Ground (G)

Change takes place during the language event, so it is represented with the jagged line. This models the short set of moments during the articulation of a specific signing or speaking act, and not (for example) an articulation event that has already finished, or that has not yet begun; in other words, G does not represent the conversation.

As a reference point, this model helps S and L to match their selection of such language items as personal pronouns (e.g., ‘us’ versus ‘them’), deictics (e.g., ‘here’ versus ‘there’), articles (e.g., ‘a’ versus ‘the’), quantifiers (e.g., ‘all’ versus ‘none’), tense/aspect and verb/subject agreement (‘goes’ versus ‘are going’), modals (‘might’ versus ‘can’), and so on. You can imagine, then, how a grounding disorder might manifest itself (if P could not self-locate relative to G), or a sharing disorder (where P could not group-locate in G). In grad school, you wouldn't have been taught to approach these issues as grounding disorders; nonetheless, that is what they are. Your therapy should be designed accordingly.

Time (t)

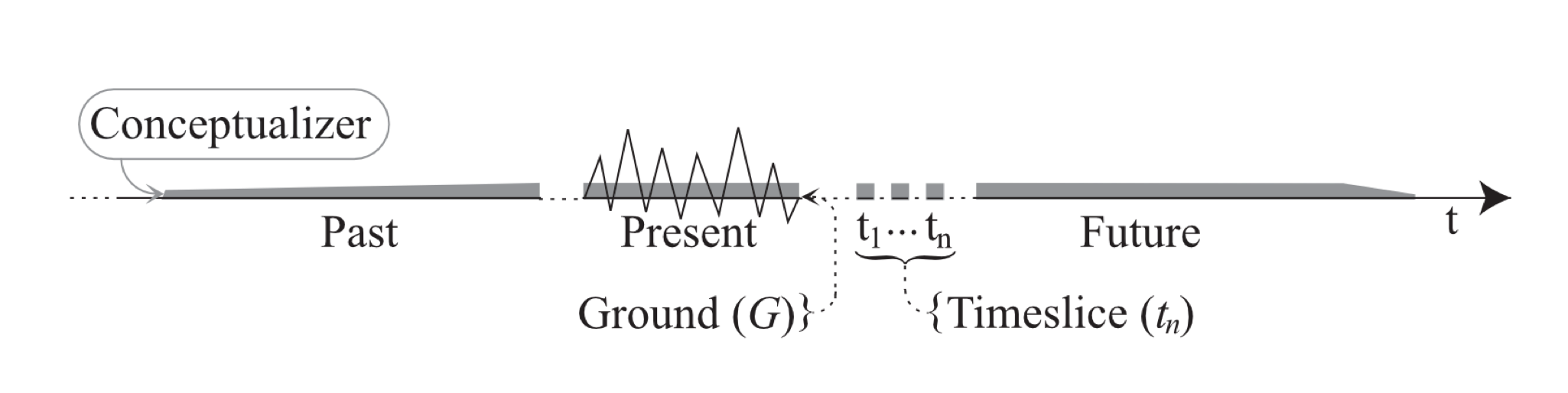

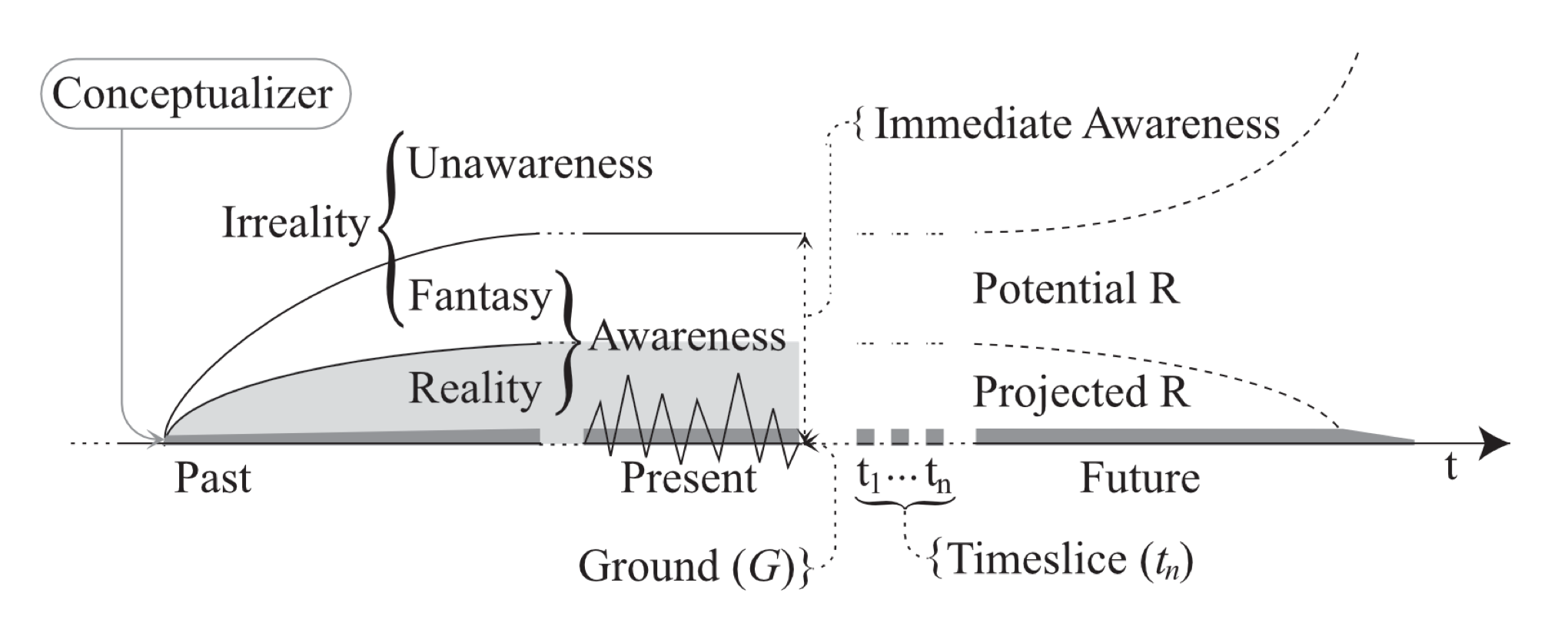

Now let’s extend this diagram to show the moments of G embedded in the timeline, with a perspective cast relative to P being a conceptualizer with a limited lifespan:

Time (t)

We note where P enters the time stream at birth, where the grey area along the timeline is their sense of self, with a ramp up as their participation increases as a thinking and physical being (i.e., as a cognizer and conceptualizer).

For languages that appeal to this sort of model, namely one of a person and their actions embedded in horizontal time (and languages do vary in this regard), this sort of grounding influences the selection of such items as tense/aspect. (Every natural language displays some sort of temporal grounding effect… that the authors know of.) Stated in a very broad fashion, Ps with this sort of language will treat any event prior to G as the past, anything during G as the present, and anything beyond G as the future.

Awareness (A) and Irreality (I)

Anything of which any P might be aware is categorized as belonging to Awareness (A).

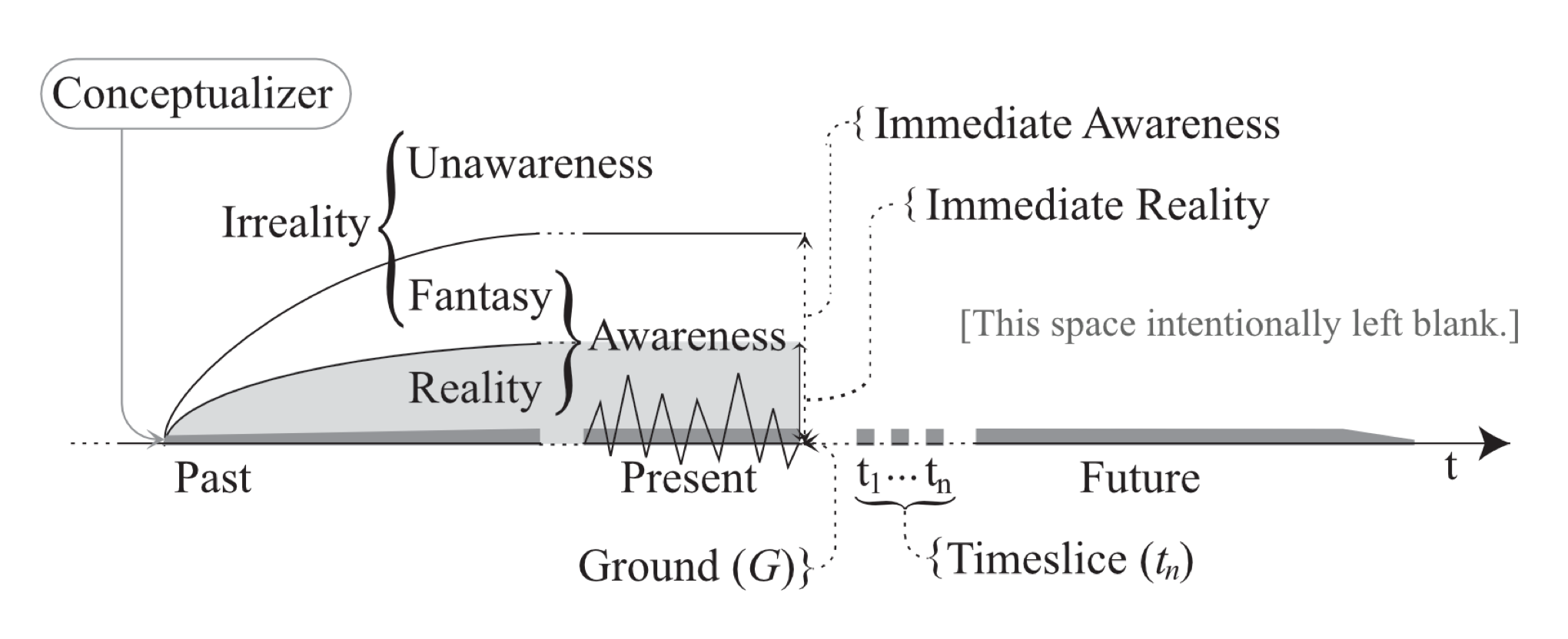

Whatever any given P is aware of, and is therefore able to conceptualize, is in their individual awareness (AP); in addition, anything that P identifies as factual is part of their model of reality (RP) within AP. This is where the categorized instance resides for that P, whether or not other Ps agree with that P about it being factual:

Awareness (A) and Irreality (I)

Everything that P does not identify as a factual component of objective reality is a member of their irreality (IP).

In this model, then, anything that lies outside of RP is P’s irreality, which comprises P’s fantasy (F) plus anything of which P is simply unaware (U), which seems a nicer term to use than “ignorance” (although that won’t stop us on occasion).

All of this renders the following equations for FOSN (Friends of Set Notation):

{A ∩ U} = ∅ (Awareness and Unawareness are mutually exclusive)

{R ∩ I} = ∅ (Reality and Irreality are mutually exclusive)

{F ∪ R} = A (Fantasy + Reality = Awareness)

{F ∪ U} = I (Fantasy + Unawareness = Irreality)

{A ∩ I} = F (Awareness and Irreality overlap at Fantasy)

While we will never use these equations in a truly mathematical way, they are nonetheless fun to list, and can help those with mathy brains to keep these notions clear; after all, we are ultimately all about the mnemonics (and other cool words that start with ‘mn-’).

There are gradients within AP; that is to say, while P identifies some entities with very stable parts of their reality (e.g., that the sun rises every morning), other entities — while still treated as real — are held to be more tenuous (e.g., that a daily breakfast of eggs might pose a cholesterol hazard). The strongest of those parts will naturally tend to define a relatively stable core (that we will discuss later as P’s “archive”).

The same gradation is true of FP; for example, P might be pretty sure that unicorns don’t really exist as biological creatures in objective reality, and yet remain unsure about the possible existence of extraterrestrial conceptualizers… or of grape-flavored gummi fish.

In some sense, there might be a gradation rather than a boundary between fact and fiction (reality and fantasy); however, whenever something is labeled as being “based on a true story,” you know that it is fiction (i.e., not actually fact). In other words, one drop of fantasy seems to dye the whole vat to fiction… while the vat is viewed as a whole, anyway. We remain open to discussion.

Caution: Sensation and perception do not always imply awareness. You can’t assume awareness based on behavior: research shows that birds (for example) will react to the sensation/perception associated with an event (e.g., something moving in their field of vision) without having actual awareness that something has happened. The simple act of the bird flying away is not evidence that it is actually aware that something is moving in its environment.

Here is the important point for intensely special education: some people are the same way, and it is considered to be a challenge for them because it is different from what most people do. So, just because a student flinches when you walk unannounced into their line of sight (or touch them when they’re not expecting it… which you shouldn’t do), that doesn’t mean that they are aware that anyone is there. While they might well be aware, it not safe to assume so.

Entities can travel within those areas over time, as P’s awareness changes; for example, P might read new research that exonerates eggs as a dietary culprit, so the earlier “fact” about eggs is reassigned as “fiction,” and gets moved to fantasy. And then that “fiction” might just as easily travel back again to reality as a “fact” at some later time. That change does not necessarily mean that such an item is stored close to the border holding between R and F; while that might happen (and there are cognitive functions to support that kind of categorization), those sorts of entities can sometimes switch from being identified as very real, and then go straight back to being treated as very unreal (and back again).

Some entities can move into P’s awareness as P learns something new, such as that “nutria” is the name of a color, or maybe that “nutria” is not just the name of a color (but rather is also an animal); similarly, entities can disappear back into unawareness (aka ignorance) if P forgets about them. The important thing to know is that material of which P is unaware is not currently available for P to reference during a communication event; that is to say, some other P would have to introduce it into the conversation (and thereby into P’s awareness).

In sum, the contents of these areas will change over time. The leading edge (or timeslice) of R as it interfaces with the future is referred to as immediate reality; similarly, there is an interface called immediate awareness. If you compare slices at different points in time, the main areas and their boundaries will continue to exist, but their contents will change (including the gradients).

And of course Ps will vary in their agreement about what should be classified where, such as in the firmness of their belief in the biological reality of Bigfoot (or the aforementioned grape gummies).

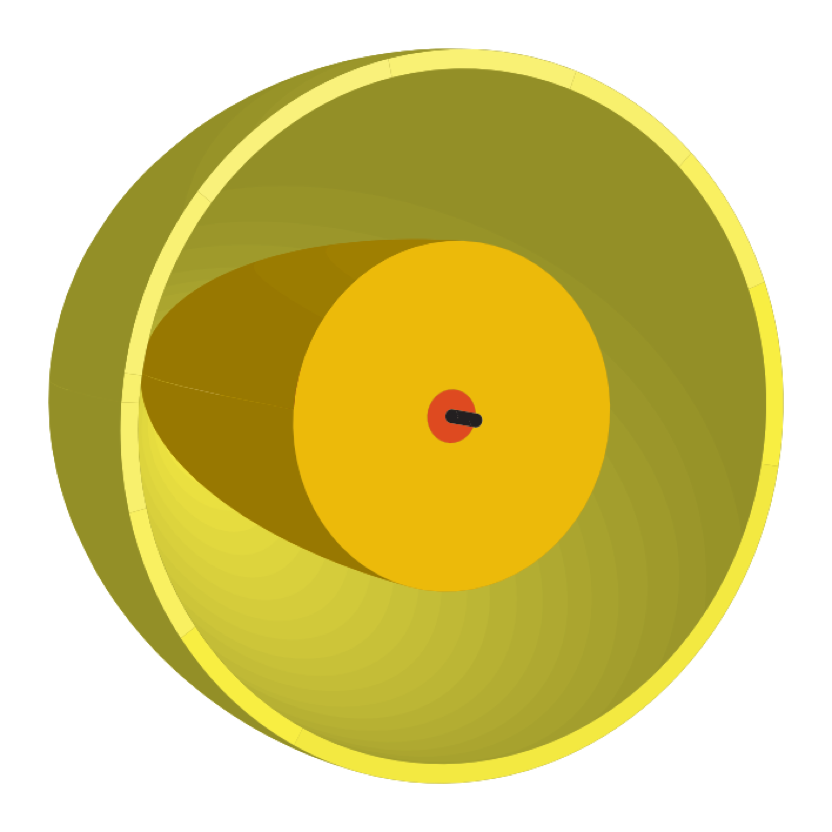

The following figure is a 3D rendition of these diagrams. It is the capsule of P’s awareness, which we portray as exhibiting radial symmetry as it extrudes along the timeline (through a Sea of Ignorance):

Awareness and Irreality (3D)

The timeline, then, is the black axis of symmetry that protrudes back into the past, and forward into the future (as based on a prevalent time model common to users of English as a language of origin). We colored P’s sense of self reddish (previously dark grey) to make it easier to identify in this figure. Similarly, R is now the relatively orange area, and F is bounded by the cheerful yellow shell. Anything located beyond the shell of the capsule resides in unawareness.

This portrayal of the capsule has been sheared off with a frontal plane at the present moment (i.e., at immediate awareness). If you were to view this model face on, it would simply look like concentric circles.

To transform this capsule back into the 2D diagrams that we have been using, you would just take a radial slice along the timeline to provide an exposed view from the side.

The use of radial symmetry reflects the strength of P’s convictions about whether their model truly reflects objective reality; in other words, P’s sense of self is the core of R, and then R is surrounded by F, rather than having R and F run side-by-side along the timeline. Of course, P would not tend to think about their convictions in those terms (unless P had been exposed to this sort of tutorial), but we will show that P’s behavior during communication events shows evidence of this type of functional organization.

Entirety (E)

This is what you get as P conceptualizes possible futures, which (as the diagram shows) are not part of established reality:

R becomes projected R (i.e., what P hypothesizes), and F becomes potential R (i.e., what P speculates). (Unawareness remains unchanged.) Notice the flange effect, where projected R shrinks as P becomes increasingly unsure about its contents the farther away that it gets from immediate reality; in comparison, potential reality fans out into a far-flung array of possibilities.

It is occasionally helpful to refer to the whole picture (i.e., awareness plus unawareness) as the Entirety (E), which has an equivalence with “subjective reality” as a whole. Then why not just call it subjective reality? Partly because ‘S’ is already used to mean speaker/signer/subject, but mostly because E is just one model (albeit a pretty important one) among the whole networked set of cognitive models that comprise P’s subjective reality (which also contains a whole lot of stuff that is not necessarily organized in terms of complex models). It is more clearly identified, then, as EP.

Just to be clear, we have not been talking about the categorization of objective reality in the development of all of these nifty diagrams of E. EP is a given P’s system of subjective opinions (about objective reality), which consists of meanings, which are not things in objective reality.

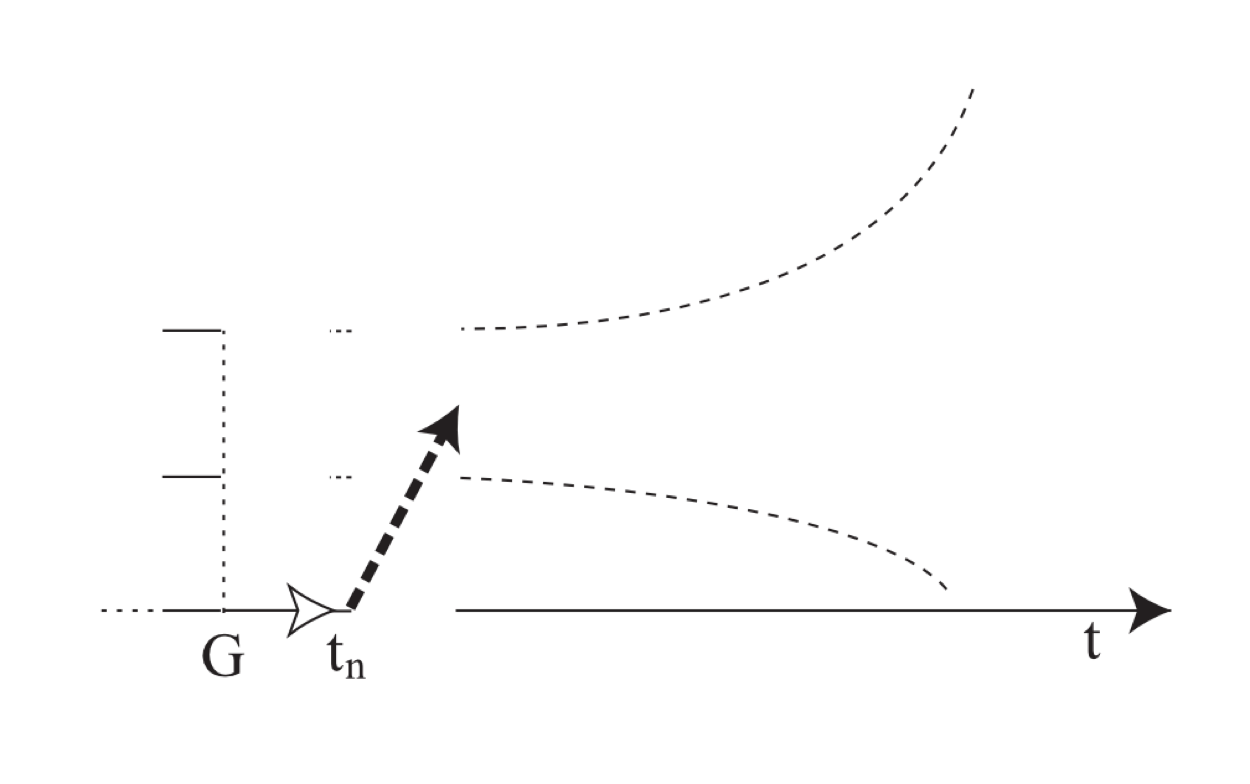

It might not be readily apparent why we are exposing you to such a complex construct without providing illustrative examples of its practical application as we add each piece. So we are going to give one example here in anticipation of explaining why we are otherwise tending to wait. The following is a model of a limited part of what happens as P conceptualizes a meaning (in preparation for taking on the role of S), where that meaning involves a concept along the lines of [MAY]:

A modal (e.g., “may,” “might,” “can,” “will,” and so on) can be used in spoken English as a verbal grounding predication (VGP); that is to say, selecting a modal (or deciding against using any modal) is one part of what S does when anchoring an event relative to G (where that event will be represented by an accompanying verb). (This epistemic meaning historically derives from, but is different than, the modal's deontic value, such as where “may” is an indicator of having permission.) That strategy helps S and L to establish mutual mental contact; for example, S’s choice of the word “may” tells L that S categorizes the event as a member of potential reality (as opposed to anywhere else in E). And whereas “ate” is an event located in past awareness, “may eat” is still just a matter of potential reality (rather than a projected one), plus it is more proximal than an event grounded by the phrase “might eat,” where that modal would be diagramed as follows:

Modal: Might

It would not be effective, then, for you to expect a student to use the word “might” to reliably refer to distal potential reality before their cognitive model reliably included distal potential reality (and the other components to compare it to); similarly, including a set of modals in a student’s AAC programming runs a significant risk of promoting clutter effects if that student does not yet share some sort of underlying cognitive model that works along the lines of E (which we have now described to you). These two cautions are both instances of the principle regarding reliable skills, which helps us to determine whether a system is being used as a training tool, or as an actual AAC system.

Again, we do not contend that anyone will have a picture of this specific diagram in mind, or even that they would process their thoughts with specifically visual imagery; the point is that the diagram represents something real that has to exist for both S and L if their language is going to work well between them.

Now, showing you this one example wasn’t so bad. And we could stop to go over the rest of the modals (and explain that the diagram’s chained arrows distinguish distal from proximal modals). But the predications in English that ground verbals also include: a) the tense/aspect system, which requires its own involved explanation; and b) subject-verb agreement, because S cannot (for example) choose a verb form to use without knowing whether it has a singular or plural subject. So, in providing this isolated example for “may versus might,” we have introduced the process of verbal grounding before we have discussed all of its components, and in fact before we have finished discussing a whole lot of other germane material. And that is the consequence of interrupting the description of the big picture.

We have made a design decision, then, to get you through the broader, underlying constructs related to grounding (i.e., subjective and objective reality) while postponing a focus on the components that they ground, because a lot of switching onto sidetracks runs a significant risk of derailment.

So we are counting on your ability to delay gratification. We promise that when we get all of this front loading finished, the explanations of how this all works will fall into place with a lucrative payoff.

And now back to our irregularly scheduled program.

Entirety (E)

Modal: May

Nonphysical Context: Awareness

Every P’s non-physical context or individual awareness (as described earlier) is part of E, which is subjective in nature; therefore, AP only exists in association with P conceptualizing. Nonetheless, despite EP’s tie to P’s subjective, personal conceptualization, P still expects material in AP to be shared by other Ps, as if it were effectively the same for everybody. That’s because P derives EP from their experience of objective reality, which P therefore anticipates is essentially the same from P to P… which is not as true as P expects.

We talked earlier about there being gradients in P’s individual awareness (Ap), where P holds some ideas to be more stable than others. P’s expectation of sharing increases with that stability; for example, the notion of ”the sun rising every morning” is so stable that P doesn’t even tend to treat it as their personal opinion. P expects every other P to share that idea as a universal fact (i.e., as part of R within A, not as RP).

Idealized Cognitive Model (ICM)

As P moves from one timeslice to the next, P updates AP, which is a cognitive model of their expectations about objective reality, based on the stability of their personal experience (which naturally includes the information that they absorb about other people’s experiences).

Stable expectations reinforce parts of the model. P will not tend to change their expectations based on occasional exceptions. The longer that something remains stable, the more resistant it becomes to change, which is known as perseverance (“per-SE-verence”). In this way, P’s models become idealized, because P has a tendency to monkey with the data to save their theory (i.e., they want to maintain their ideal, so they ignore exceptions to their ideal rules... so they take a formalist approach to reality).

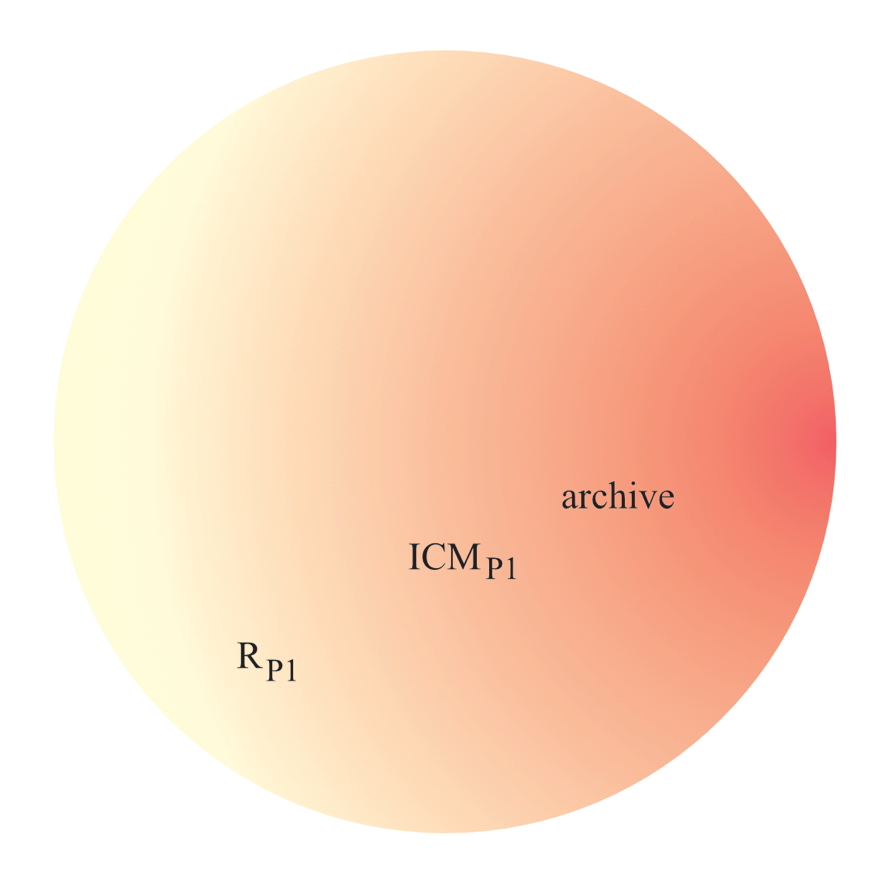

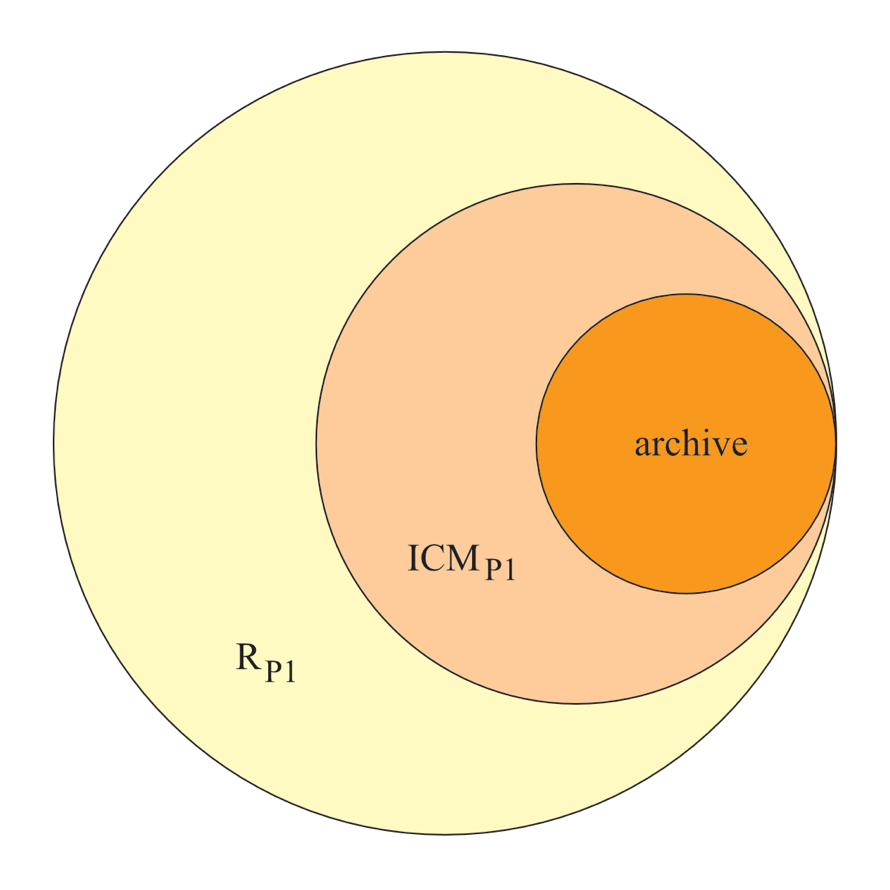

That stable subset of RP is described by P’s personal set of idealized cognitive models (ICMP).

P’s individual archive (small ‘a’) contains their system of ICMs, and it is the store of those things about RP which P holds to be resistant to change. Some of P’s cognitive models will be more thoroughly idealized than others, so it can be more helpful to look at P’s archive as containing those ICMs that represent greater resistance to change, rather than the set of all ICMs.

Even though ICMs represent some amount of stable reality, ICM overlap between Ps tends to be less than they assume, and is further reduced (significantly) in intensely special education, so even less can be taken for granted as “given” when Ps try to communicate.

In the following diagrams, darker color signifies greater stability (whether as a continuous gradient or in discrete areas):

P1’s archive in RP (Continuous)

P1’s archive in RP (Discrete)

The actual stability distribution is best understood to be a hybrid between (a) smooth, continuous gradients and (b) sets of nested, discrete concentrations.

Note that “stable” does not mean “highly likely to occur”; for example, there are conventional notions insisting that anyone can win the lottery, or that anyone can become President of the United States. These ideals are maintained as stable despite the low expectation of seeing them realized, and P can support them right alongside a high expectation that they will not be realized; in fact, that they are not realized is yet another ICM. So, something which P expects to never happen might actually happen on occasion; it just might not happen often enough to change P’s expectations about the likelihood of its occurrence.

P should expect things from their individual archive to be ‘given’, ‘obviously true’, or ‘not open to question’, so their archive is a location to which P readily refers during a conversation. Mansfield (1997) gives evidence to suggest that this intuition about archival knowledge being ‘given’ is so strong that each of the participants in a conversation (P1… Pn) will expect their individual set of archival knowledge to be shared entirely by all of the other participants, the main point being that this is a false consensus because their individual archives will necessarily intersect much less closely than any of them expects.

The Archive (X)

It follows that archival ICMs should tend to be similar from P to P since they are all building expectations about what the same objective reality is like. Different Ps should find a core of similar things to be stable about objective reality: gravity keeps you on the ground, other drivers are inconsiderate, and bees are great. ICMs dealing more with discourse tell you that when you want to refer to something, you point to it somehow, or you point in the direction of its location.

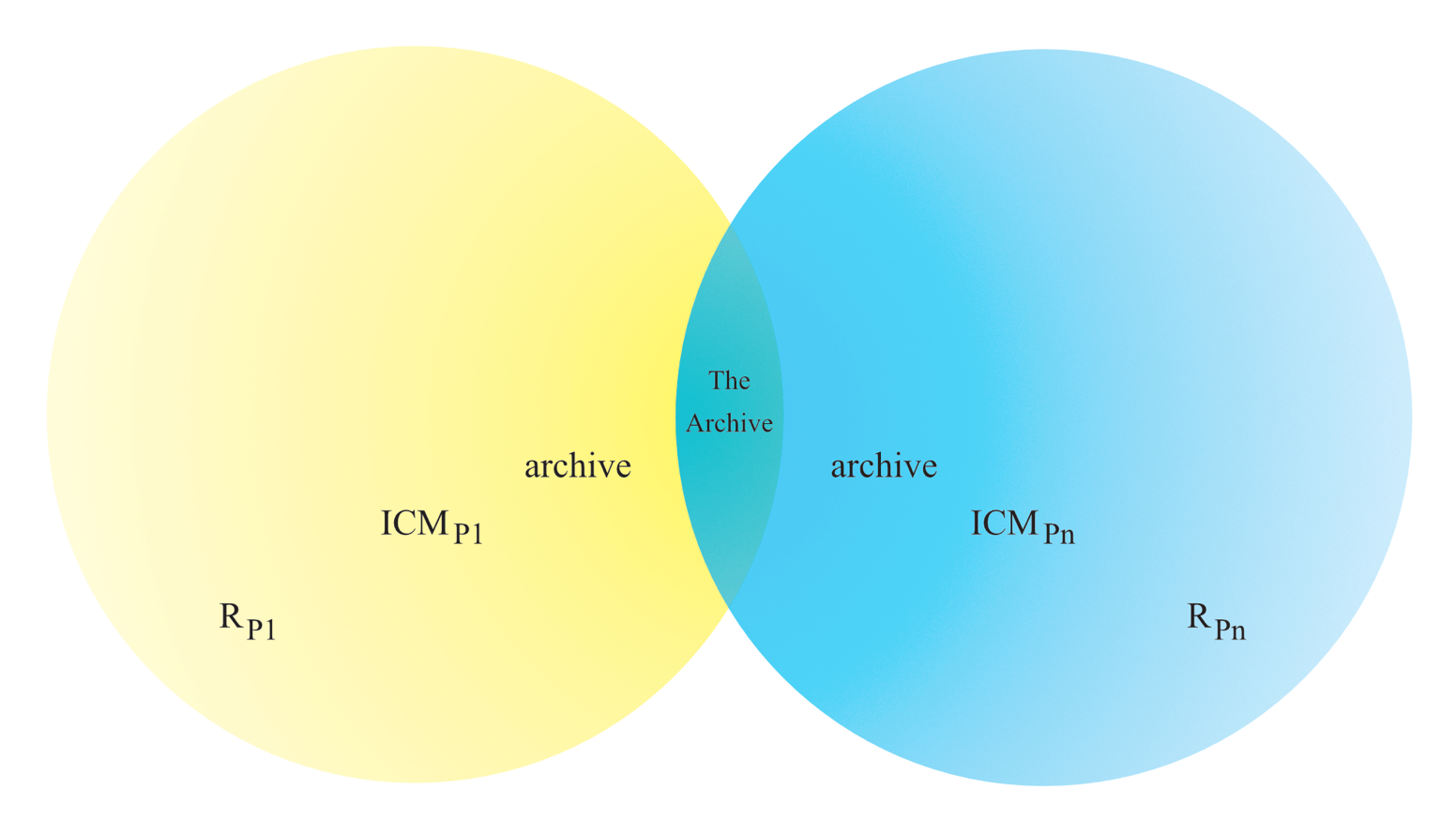

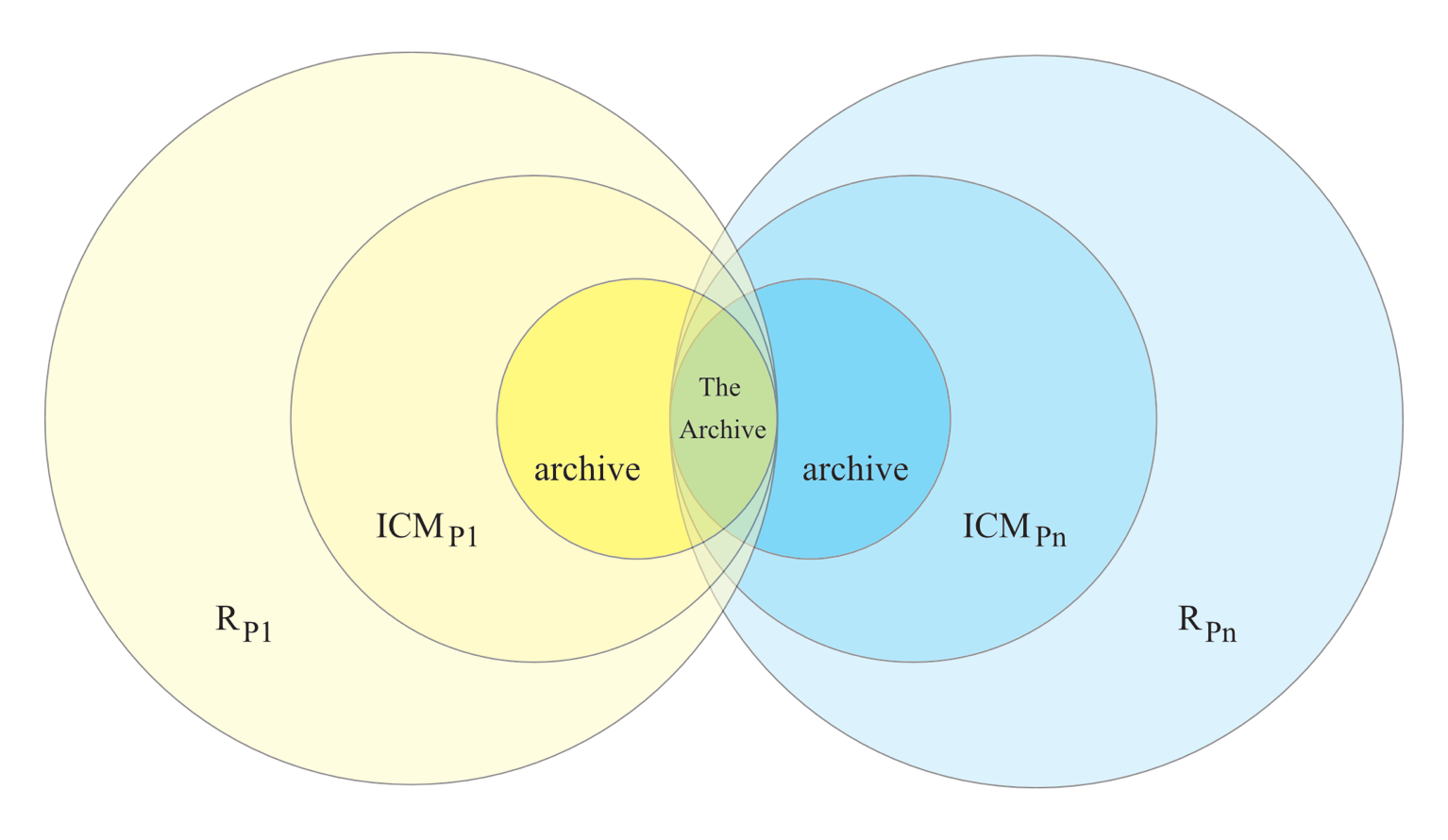

These are all intuitions that will tend to hold from P to P; however, to the extent that their archival knowledge is different, it becomes necessary to distinguish between any given P’s archive and the core of archival knowledge shared by any given set of Ps. This communal core is the Archive (X for ‘intersection’, since we already use A for Awareness), and it is naturally the material in the intersection of all of the individual personal archives.

Just as there are central and peripheral densities in our perception of the world, the archive has areas distinguished by their accessibility. Chafe (1973) first describes this viscosity in terms of a familiar depth-continuum, defining surface, shallow, and deep memory; later on (1994), he modifies this portrayal to align better with his newer descriptions of active, semi-active, and inactive states of consciousness (ch. 5). In both works, Chafe shows that there are normal sentence structures and intonations designed to plumb each of these three depths or activation states.

Chafe’s earlier work suggests that specific prominence patterns can be used to reach particular depths of a cognizer’s memory, and he says in the later work (ch. 6) that accessing less active information exacts a greater activation cost, and prominence is an expression of that cost. Not only would activation of one’s own inert memories (as experience for distal events) be costly, but so would activating any equally inert memories in someone else through the energetic articulation of prominence. This cost is in direct proportion with memory or inertial depth. The coin of the realm is quanta of energy, which intense prominence spends in an iconic expression of energy. It takes that energy to recruit muscle fibrils during articulation, for example, more of which is required for expressions of greater prominence.

One cognizer can even pay the cost of a proximal event, activating deep or inert material in another cognizer’s mind, which brings us to the discussion of cognizers working together as a group.

As some number (n) of Ps engage in a shared event, they each contribute their non-physical context, namely their personal awareness (i.e., AP1 through APn). Within that awareness, they will tend to focus on the contributions of their personal realities (i.e., RP1 through RPn). The following diagrams illustrate the immediate timeslice across two RPs at a given moment of their mutual interaction (where color intensity signifies increased stability):

Reality and the Archive (Continuous)

Reality and the Archive (Discrete)

So this is what happens non-physically as P1 approaches an event that will be shared with Pn. Again, the actual stability distribution is best understood as a hybrid between (a) smooth, continuous gradients and (b) sets of nested, discrete concentrations.

Further discussion will be deferred until after we have provided a similar explanation of objective reality, as follows.

Objective Reality (O)

Each and every P lives in just one objective reality (O) that is shared with each and every other P.

Naturally, there is controversy surrounding the notion that we all share one O. We suggest that you build a solid familiarity with this tutorial before moving on to those alternatives, as their resolution likely will not affect your development of therapy.

The argument in favor of O’s objective reality (which, yes, is ironic in some way) is that nearly all of the universe would exist even if nothing had the ability to conceptualize; in contrast, all of the stuff that comes of conceptualizing is subjective reality.

O would exist even if the ability to conceptualize had never existed in the universe at all; similarly, O would continue to exist even if the ability to conceptualize entirely disappeared. O, then, is what exists without regard to any meaning arising from conceptualization. So, if you get rid of what it all means, then just the interrelated stuff remains. Similarly, there is no timeline, in that the immediate moment in the present is all that actually exists for O (i.e., the rest of time, as a memory or a future projection, is a subjective construct, and so does not exist without subjects to construct it… even if “the present” is not represented by the same moment everywhere in the universe).

These statements are intended to establish a highly schematic base of agreement for the further description of O, one which is fundamentally consistent with a wide variety of elaborations (e.g., “Prime Conceptualizer,” “brain in a vat,” and so on). We take no substantive position on an SLP’s personal choices among those specifications, as any resolution among them does not affect the development of therapy. We would be blithe to engage in such ancillary discussions after you have completed this tutorial.

For example, an entity such as “the potential risks posed by any dietary properties that are associated with eggs” has some sort of valid, objective existence that is entirely independent of any conceptualization in which any P (human or otherwise) might engage. So that existence holds without regard to any subjective opinions formed by any given P (as does the existence of eggs, diets, hazards, and their associated relationships). It would exist even if every P lost its ability to conceptualize.

In other words, that particular property of eggs is either a member of O (i.e., it is a fact), or it is not a member of O (i.e., it is fiction), no matter what any P thinks about it.

This status as a member of O can change (relative to a given section of time); for example, we know that (as of this writing):

• dinosaurs no longer exist on Earth as a living species in O (except as birds),

• passenger pigeons no longer exist as a living species in O (even as birds), and

• the large cactus finch has recently come into existence in O as a living species (among all other species, including birds).

This status of an entity relative to O does not change due to what P conceptualizes. P’s thinking about it does not bring it into existence in O, and the entity does not disappear from existence whenever P stops performing as a thinking being (for one reason or another).

There is some research that claims to dispute this contention as well, suggesting that thoughts can directly influence reality, but again, we would suggest your leaving that until later. And, of course, if you work from the perspective of a belief-based framework then this discussion changes radically. While we do not deny the validity of belief-based frameworks, we are not using one here. This choice does not affect the development of evidence-based therapy.

Here, then, are a few things that are part of O:

Bigfoot books

Bigfoot drawings

Bigfoot statues

Bigfoot costumes

Bigfoot movies

bears

the universe

The Academy Awards ceremony

And here are a few things that are not part of O (as far as we can tell at this point):

evidence contributing to valid proof of Bigfoot

valid proof of Bigfoot

Bigfoot

grape-flavored Swedish Fish™ that are actually made by Malaco

This leaves us to clarify the nature of P’s thoughts and feelings about Bigfoot, which can exist. The form of that thought would be a member of O, to the degree that it is a “snapshot” of a dynamic activation pattern occurring across an electro(neuro)chemical network that we will call “cracklin’ wetware” (on occasion). The meaning, however, would not be a member of O, as that would only be the subjective opinions that arise in association with that wetware. So while that meaning does exist, it does not exist in O. (We somewhat discussed its existence in subjective reality earlier, and will do so in more detail later.)

So, while P does not bring an actual Bigfoot into O by thinking about it, the form of P’s Bigfoot thoughts exist in O for the duration of P’s thinking. This cracklin’ never stops altogether in the wetware of a healthy P.

It is beyond the scope of this tutorial to explain what is happening as P exerts “direction” (or something functionally like it) over its cognition, in large part because there is no viable answer to give. We know that:

• there are executive functions associated with the likes of focus of attention, (dis)inhibition, and so on, and

• the availability of certain neurotransmitters can affect our ability to use those executive functions well, but…

that doesn’t really tell us how we exert control over those control functions without getting circular in our reasoning. We know how it feels to direct our thoughts, and we can practice techniques to improve concentration (and so forth), but we don’t fundamentally know what we are doing when we cognize, or engage in conceptualization. There are a whole lot of guesses out there, but no reliable answers (yet).

What follows is another cognitive model of O (which we will call Eo), whose existence is just as subjective as the earlier model of the Entirety (i.e., Es); however, they each model different likelihoods:

Es: that P has an opinion about something’s existing in O, versus

Eo: that P has actual, physical experience of something in O.

You can understand how the likelihood of something being experienced in Eo is tied to a likelihood of how it gets categorized subjectively in Es.

This distinction should become clearer as we proceed.

The World (W)

There is a whole lot of O that has never been physically sensed by any P, such as: the cold of absolute zero, colors that require more than four cones, scents for which humans have never had olfactory receptors, processes occurring within our own bone marrow, and so on. (We don’t really have a need to designate that set with a label.) Some of that objectively real stuff will never be accessible. Everything whose signals are potentially available for reception is a designated part of the World (W), as a subset of O.

While some signals are inaccessible through our innate sensory array, they can be made available through the indirection of tools (e.g., scopes of various kinds, drugs that alter sensory capacities, and the like), so those signal generators are also part of W while those tools are in use; for example, something that you see through substantial aided night vision is only part of W for you while you are using your night vision goggles. (When you take the goggles off, that same thing remains part of O even though you cannot see it as part of W.)

It can be helpful to distinguish (a) the set of signal generators that are external to the body from (b) those that are internal, and we went into greater detail about that topic earlier in this tutorial (in the section on sensation).

To the degree that brains have signals acting with objectively perceivable effects (i.e., thoughts and feelings), those forms are part of W (along with their electrochemical processing events), even though their associated meanings are not (i.e., their meanings are all subjective).

This should all be recursive, in that the generators whose signals we are receiving exist in O, and they are receiving signals from other generators, and so on. In that sense, O should include all such entities, whether we experience their signals directly, or they are just part of the infrastructure without which none of this would be happening (i.e., their signals, or their consequences, are potentially available). Fortunately, we don’t need to be overly concerned here with such deeper philosophies.

Everything (E)

Add all such considerations together and we can posit this cognitive model of O called Everything (which we identified earlier as Eo, so as not to spoil our big reveal). Clearly, Eo is a lot less internally complex than the Entirety (Es, in case you’ve forgotten). Again, Es is a symbolic structure, so the physical form that supports Es (i.e., the cracklin’ wetware) is part of Eo, but the meaning of Es is not.

One big difference between the Entirety and Everything is that physical accessibility is (as far as we know) inapplicable to the past and the future. There is no physical, objective timeline, so there are no projected or possible states of O to exist as part of Eo. All of that sort of stuff only exists subjectively, in the Entirety.

Which is why we began this explanation with Es, namely: Ps converse as if O extended through time (one way or another), so their cognitive models of O incorporate a temporal dimension (generally with projected and possible futures), so it is better to diagram out the more comprehensive model in full, and then reduce that template to match the needs of its more restricted relative.

And now we are ready to move forward.

Physical Context

P’s individual physical context, then, is part of W (i.e., WP or P’s small-w world); therefore, P’s personal world exists whether or not P is conceptualizing. (P’s world is a very small part of W, and a vanishingly small part of O, but to P it is significant.) When P’s experience of their world gives rise to conceptualization, it influences P’s personal model of O, as we have discussed.

P expects their world to be shared by others essentially as if their world were W: if P feels wind, then they expect other Ps near them (i.e., P1… Pn) to feel wind as well; if they see a tree, then they expect it to be seen; same thing if they taste something sweet, or feel something soft… ad somnium.

Even when their worlds do overlap (while everyone is experiencing the wind together, or whatever), there will still be degrees of difference in their worlds that arise from such pragmatic factors as Ps facing different directions, or from a given P not using one or more of their sensory modalities (due to nasal congestion, blindness, and the like).

The physical aspects associated with P’s body (e.g., that their heart is racing) is part of their world, but what such forms mean to P will be not be part of their physical context (e.g., “I am anxious,” or, “It’s not a heart attack”). Those meanings are part of Es.

And even when the shared sensation is similar, the individual perceptions might not be. Whereas P1 might experience physical discomfort due to the noise in a particular environment (WP1), Pn might only experience comfortable or neutral reactions (WPn). (Again, this is just the physical experience, and not what that experience means to either P.) Even though there is only one set of noise conditions in W, the individual experiences of that environment differ from P to P, so their personal physical realities (i.e., their worlds) are no more than similar (WP1 ≈ WPn).

Universal Somatosensory Experience (USE)

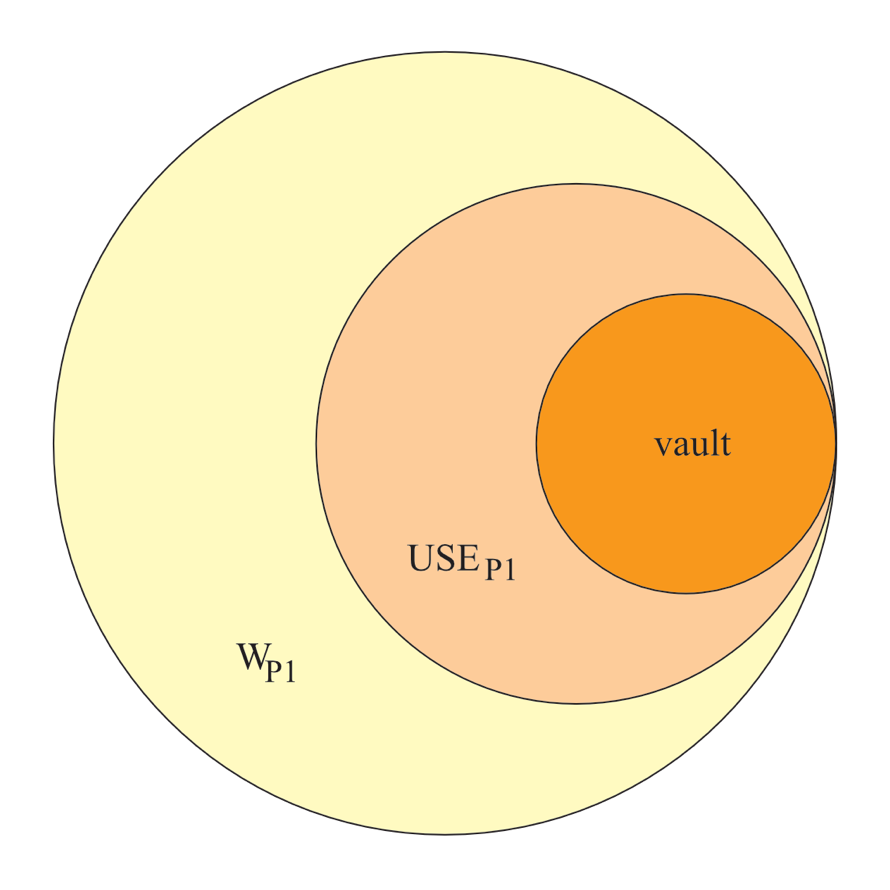

Any particularly stable form in P’s world (e.g., that extreme sensation is always painful) is more likely to belong to a pattern of physical experiences that will be shared in common with other Ps, where we refer to such forms as a universal somatosensory experience (USE). The most stable of these USEs will belong to a collection that we will call the vault (i.e., this is parallel with ICMs and the archive).

A USE might be more likely (than an unstable pattern) to influence a shared event in a couple of ways:

• without needing to associate these forms with meanings, the behavior of the involved Ps will tend to reflect this shared experience (e.g., their shared avoidance of extreme sensation will tend to occur without explicit communication); and

• these forms are more likely to contribute to meanings that are also shared among Ps, such as the conceptualization of extreme sensation as always being painful.

This latter consequence was discussed in the section on idealized cognitive models.

Note well: As with ICMs, USE overlap between Ps is (significantly) reduced in intensely special education.

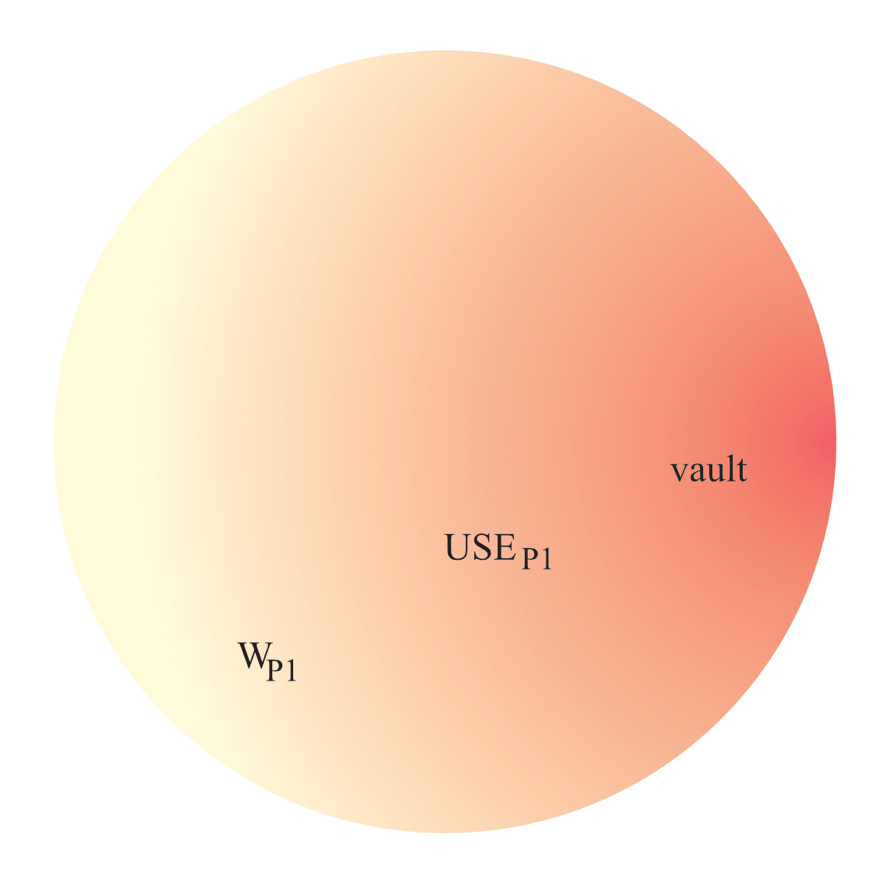

In the following diagrams, darker color signifies greater stability (whether as a continuous gradient or in discrete areas):

P1’s vault in RP (Discrete)

P1’s vault in WP (Continuous)

Within P’s world (WP), USEs represent some stability, and P’s vault will be the location that holds the collection of P’s most stable USEs. The actual stability distribution is best understood as a hybrid between (a) smooth, continuous gradients and (b) sets of nested, discrete concentrations.

The Vault (V)

The Vault has a structure similar to that of the Archive.

USEs in the vault should tend to be similar from P to P since they are all experiencing the same O. Even at that, Ps will differ in their identification of which experiences are most likely to be the most stable; therefore, for any set of Ps grouped together for an event, the Vault (V) will be the intersection of all of their individual vaults; that is to say, it is the set of all of the USEs that they are most likely to experience in common.

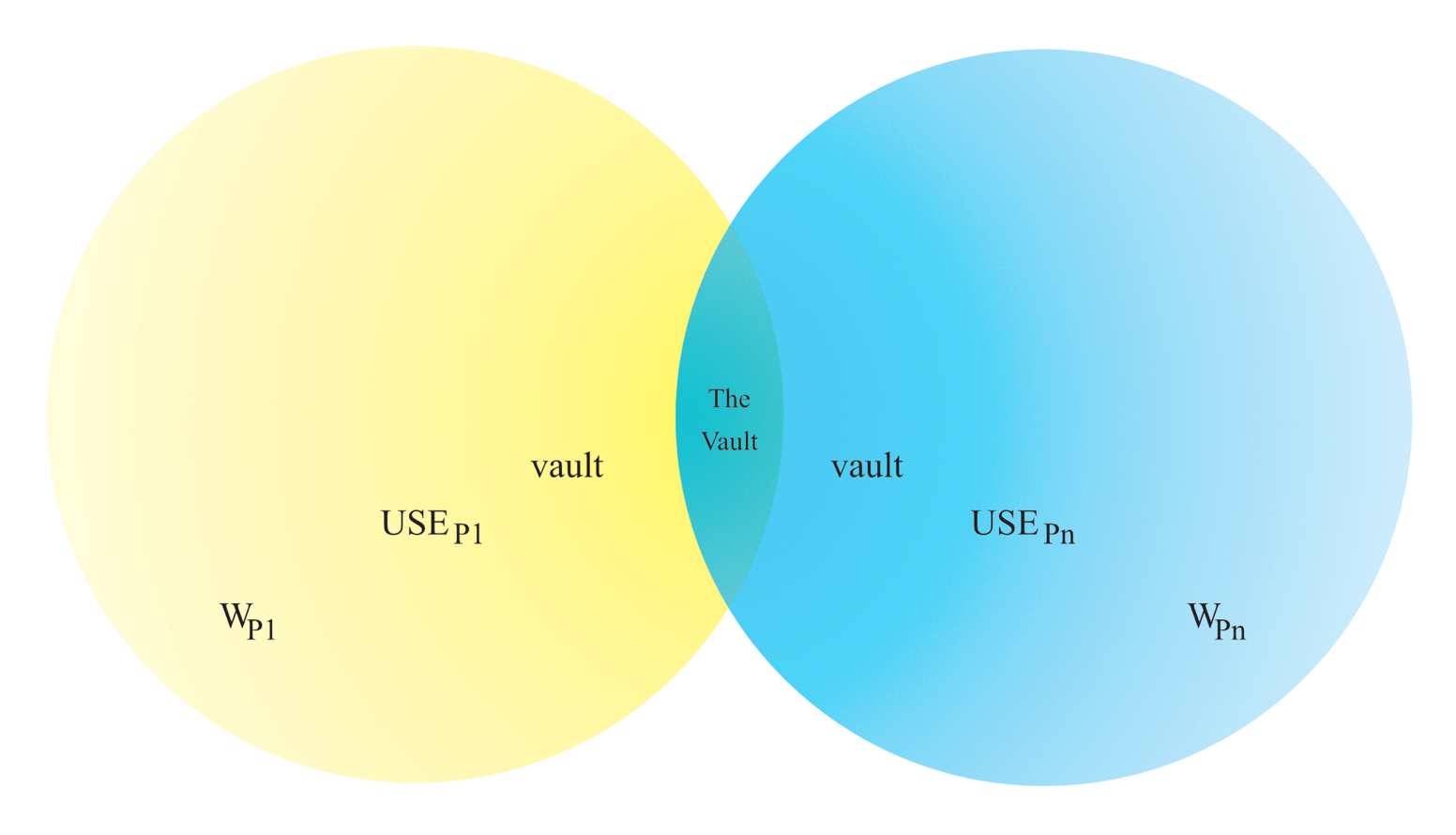

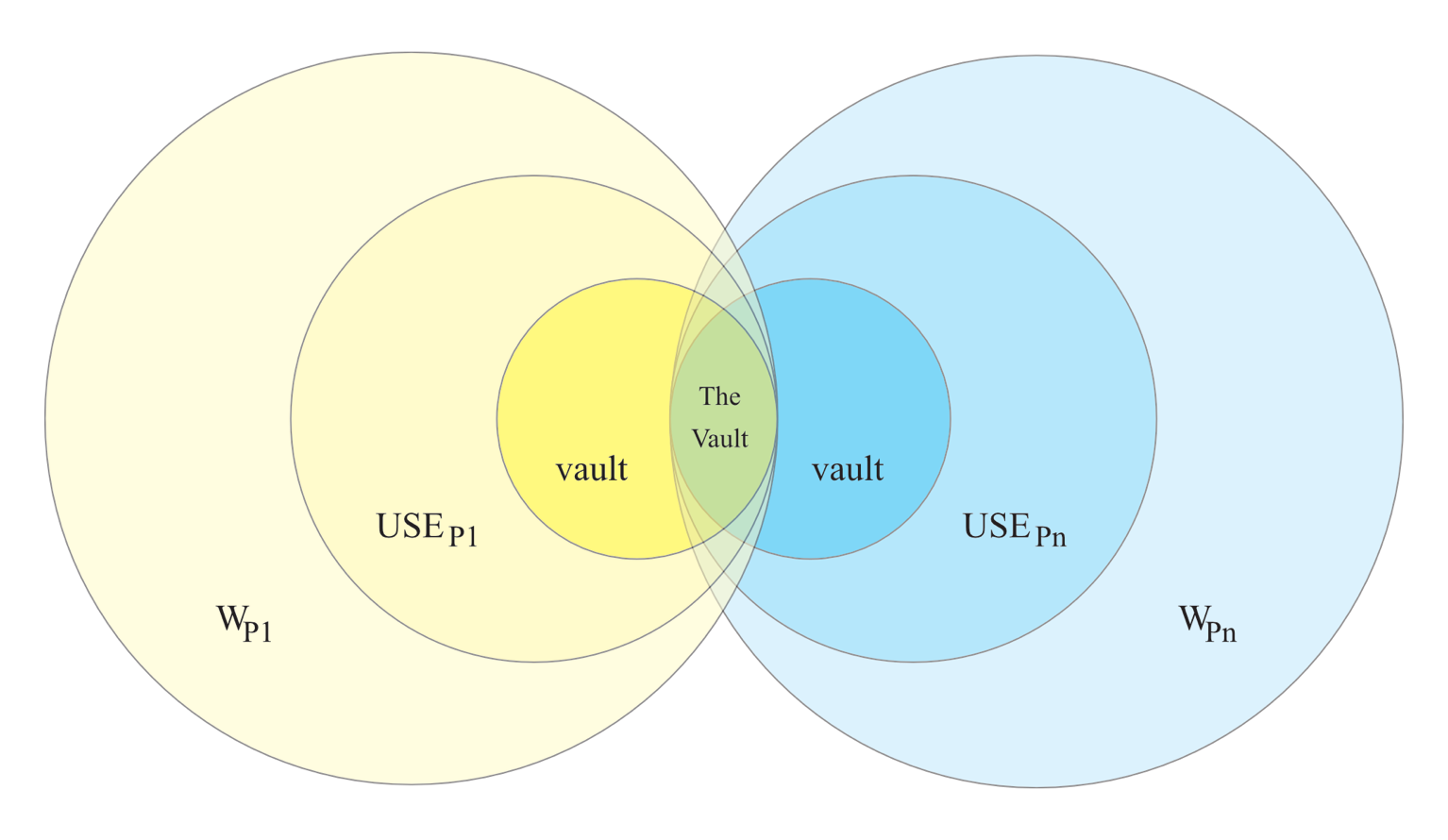

The following diagrams illustrate such an overlap:

The World and the Vault (Continuous)

Deeper color saturation still signifies greater stability, but we switched to blue and yellow gradients with more transparency to make their intersection more evident. As with their non-physical counterparts, the stability distribution is a hybrid between continuous gradients and discrete concentrations.

Now we are finally ready to discuss what happens when Ps collide.

The World and the Vault (Discrete)

Conversation

Conversation is mind blowing:

1. A conceptualizer has a meaning in mind that is associated with a form, where it articulates that form into its shared environment (i.e., it generates a signal).

2. Another conceptualizer receives that signal from its shared environment, which evokes a meaning in their mind.

3. Both conceptualizers end up entertaining similar meanings.

4. Such exchanges continue reciprocally, sometimes at great length (often involving repair strategies along the way).

Functional communication, then, is a meeting of the minds. That this process works even as well as it does is frankly astonishing.

That meeting emerges from cognitive processes that establish mutual mental contact with information. One of those processes is the creation of the current discourse space (CDS), and another is an appeal to the objective scene (OS), both of which are detailed below.

These topics are also covered in Langacker (and elsewhere), but we will try to simplify it all with smaller steps and more examples. While our versions might take longer to get through, we are more likely to make it to the end without losing people along the way (or requiring multiple readings).

This is our goal, then: less nope, more hope.

Current Discourse Space (CDS)

When people converse, the roles of S or L will usually be passed around from P to P, and a temporary model of reality or discourse space (DS) will be created for the purposes of conversation. The contents of the Archive plus the Vault (i.e., {X ⋃ V}), plus the information from earlier stages of the discourse (if any), all add together to make the current discourse space (CDS). This communal construct creates a broad “playground” for mutual mental contact, which is then refined as follows…

The CDS is updated frequently as people converse, on a faster than per-clause basis, and the most recently updated portion of the CDS is called the immediate discourse space (IDS). The construction of the specific initial state of the CDS (i.e., CDS0) begins before any symbols have been expressed. It is the state of the CDS which exists before any conversant tries to update it by taking on the role of S and drawing something into it from the surrounding contexts (physical or non-physical), or by referring to any instance which already exists in CDS0.

In short: {X0 ⋃ V0} = CDS0.

In long, the physical context includes anything of which all of the conversants share a current sensory perception in their physical surroundings, and the nonphysical context is the intersection of all of the conversants’ personal views of reality, so the initial state of the CDS includes anything in the physical context which provides sensory experience for all of the conversants (warm sun, rough floor), their perceptions of these stimuli, plus the core of archival knowledge shared by all of the conversants. The initial state of the CDS is the set of all entities (types, instances) of which the conversants are already mutually aware just prior to the beginning of any discourse, so those entities do not need to be drawn into the IDS by any form of elaboration.

One important priority in this tutorial is to make the material in that paragraph clear. We should bring you to understand everything that goes into a typical conversation even before the participants actively engage. In special education therapy contexts, there will of course be some mismatch between Ps (just as there are in any conversation), but compare (a) that typical expectation to (b) what occurs when X and V are moderately-to-profoundly different for one or more of the Ps. Think about what you would need to include in the design of informed therapy to scaffold those expectations. Your therapy should help a conversant and their partners to establish a sufficient overlap of mental contact.

This temporary model is any given P’s CDS, and it lives for the length of the conversation. Since no two people actually use the same brain, each person must have its own CDS, even though people behave as if they were manipulating only one CDS between them. Again, this feeling of being in consensus about shared information is strong, but always at least partly false; however, to the extent that the people are supposedly building a shared body of information between them, we will refer to the CDS as if it were one entity, rather than a set of multiple, overlapping, near-identical copies, with one copy being distributed to each person. Such a view does not change this analysis, it merely makes the CDS much easier to discuss.

Given this definition of the CDS, it is surrounded by (and is a subset of) its context, which is the union of its physical and nonphysical contexts. The set of information known commonly by all of the members of the group (the intersection or Archive) is a subset of the sum of the information known by all of the members of the group taken as a whole (the union). The physical context works in a parallel fashion. S can update the CDS by drawing new material into the IDS from the context of the discourse, including material drawn recursively from older stages of the CDS which have fallen farther away from proximal time as the CDS is updated. Some of this new material has the potential to update the Archive in general, and therefore the archive of any P involved in the discourse.

Objective Scene (OS)

(This next part is clearest when written in terms of “I” and “you,” after which we will return to a more standard register.)

Generic awareness is rather passive and vague; for example, I “kind of always know” that I perpetually have things to do, even when I am not actively thinking about that fact (of consistently having things to do), or about a specific item on that list. In comparison, conscious awareness is more active, and less fuzzy; that is to say, I can identify the cleaning of litter boxes as an indefinite chore across the decades of my lifespan, and devote some conscious awareness to the fact that this task has involved various litter boxes over the years, where those litter boxes then define a schematic type of entity that is always an element in that scenario. I know that litter boxes exist, then, and I think about them as a class of entity (and can bring specific instances to mind).

Beyond such notions about types of chores and elements, I have individual conscious awareness of the specific litter box that I have to clean this evening during a specific instance of that duty. Given the imminence of that chore, I have current mental contact with that specific litter box right at this very moment. And now you do too. You now have individual conscious awareness of the specific litter box that I have in mind as well (i.e., an instantiation of a type). While it might not “look” the same in my mind as in yours, there’s a specific litter box in your mind all the same (well, if you know what they are, and have any experience of any), and yours is identified with the one that I have to clean this evening.

All sorts of language processes (in that written paragraph) helped us to establish that mutual mental contact.

That said, it would have been a lot easier to come to a meeting of the minds if we had been sharing the same ground (G) locally, and I could just have pointed to the specific litter box, or signed/said, “that litter box,” “this litter box,” or — my exceedingly rare favorite — “your litter box to clean this evening.”

Whatever you are conceptualizing is getting some of your attention, whether vaguely automatic or deliberately volitional, where we have previously discussed focus in terms of profiling and prominence. Such functions narrow down the scope of reference and help minds to meet on the same targets.

There are many clarifying metaphors that address this notion of attention. We will be using one about a theater, which involves such components as actors, an audience, a stage, props, focal lighting, and so on. Again, this doesn’t mean that you have the neurostructural equivalent of a theater in your head, but rather that conceptualization relies on some sort of constituency that provides these functional roles; for example, if you have read the material on technology in education that is posted on Lane ESD’s website (for example), then you already have some familiarity with the distinction between “subject” and “object” in terms of jectivity.

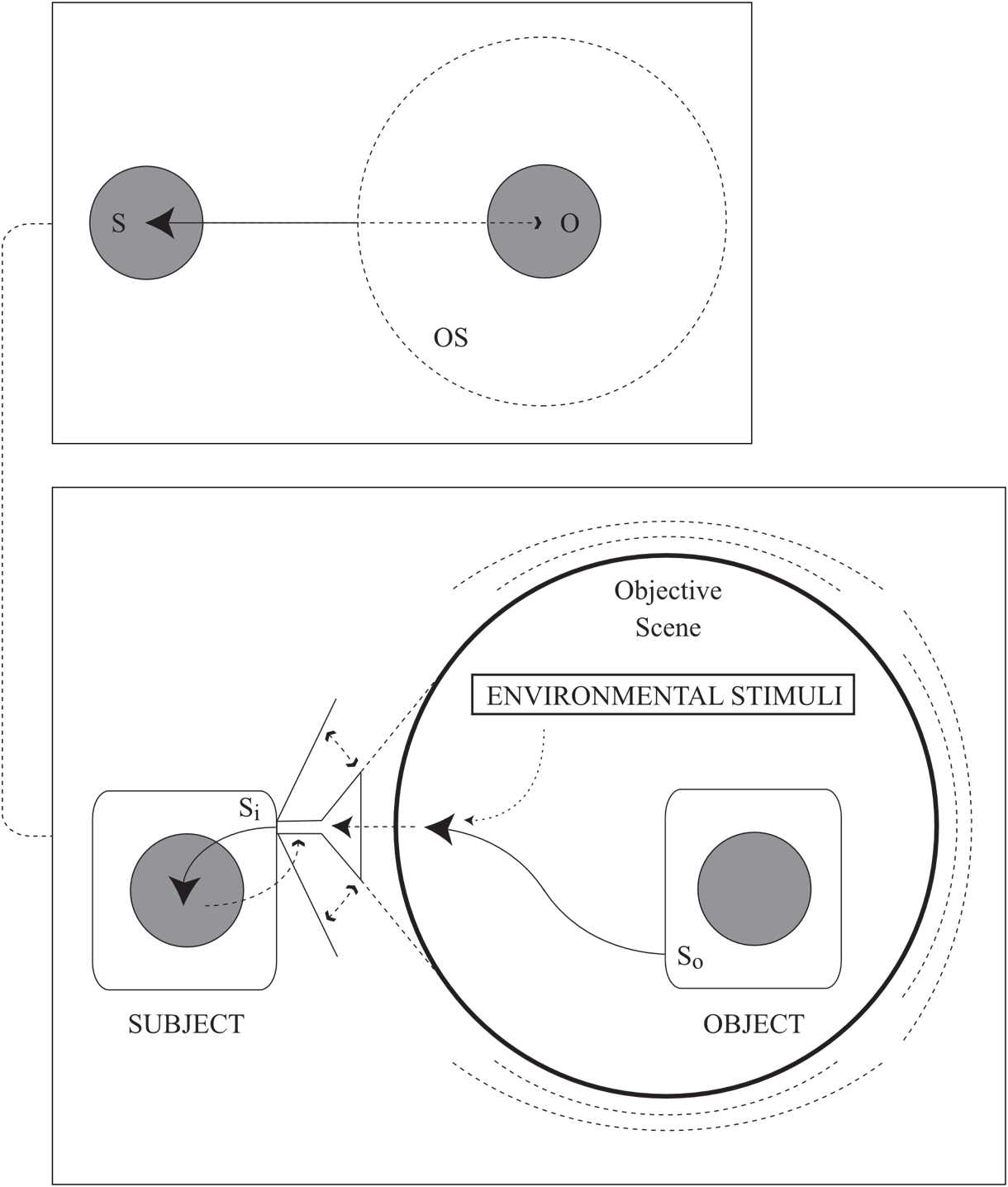

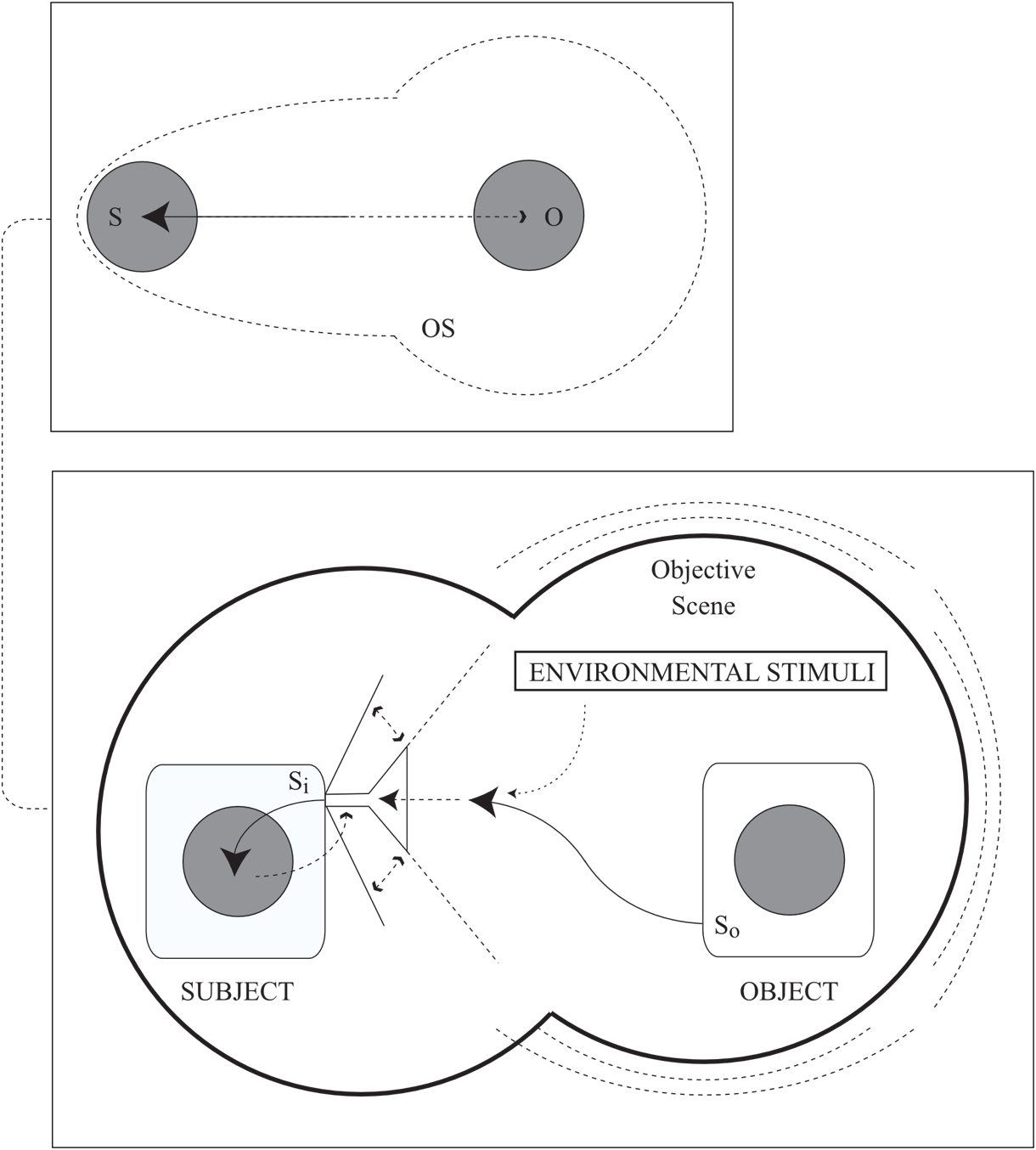

So let’s start with the maximally objective scene, where a subject is perceiving objects on the stage. As a “construer of content as meaning” (i.e., as a conceptualizer), any P can act as a subject:

Objective Scene (Maximal)

(The notion is that both boxed diagrams represent the same thing, but the lower is more detailed.)

When we use the terms “subject” and “object” here, we are not talking about grammatical roles; that is to say, we are not referring to something like the subject or object of a verb. We are discussing an aspect of construal, namely the subjects and objects who participate in an event of perception, namely the Ps who are taking turns being the perceivers and the perceived.

In the maximal objective scene, S only refers to things on stage, so they are not themselves the object of any of their expressions. Such perceiving subjects are not referred to in a conversation in their role as subjects, but rather such subjects make reference to perceived objects.

But let’s say that P uses a word like “I” (or entertains that meaning even without expressing it overtly). When that happens, then that perceived aspect of P becomes an object of P’s own attention (while the referent of “I” remains a grammatical subject). In such a case, the objective scene is no longer maximal, but rather it “erodes” to envelope the subject to some degree:

Objective Scene (Eroded)

If a conversation is like a theater play, then P1 saying “I” moves P1 from out of the audience and onto the stage (overlapping the grammatical subject referent), where the other Ps can then also refer to P as an object of the group’s perception.

Basically, when you are acting as a subject, then everything else is an object. The subject is the experiencer, and the object is the experienced. The subject is the user, and the object is the used.

But when an object behaves more like a subject, then it is subjectified.

And when a subject behaves more like an object, then it is objectified.

Time for an example.

Let’s say that you, as a subject, have relatively typical vision, and you are outside on a sunny day. (This example would work just as well with any other exteroceptive sensory modality.) You are looking at some objects at a distance away from you, perhaps flowers. (Aw, how pretty.) You have sunglasses in your hand, and you can see those as well, so they are also objects.

You put on the sunglasses and the world around you appears to be darker, including the flowers. You are initially aware that this is an effect of the sunglasses, so the eyewear remains objective, albeit not as objective as before you put them on, because now most of your visual experience is filtered through them (as if it were a part of you as a perceiving subject).

After a while, you might become less aware of the sunglasses as something that you were wearing, which would make them even less objective (and more subjective). When you get to the point where the world itself seems dark (i.e., as if you were simply a perceiving subject in a dark world), and you forget that this darkness is due to the sunglasses, then they have become primarily subjective. Take them off and they are suddenly once again an object.

Similarly, if you were wearing contacts (or had intra-ocular lens implants), then you might be even less likely to think objectively about their affect on the appearance of the world. They would be an integrated part of your subjective perspective.

So, when an object is absorbed into a subject’s experience, and becomes part of the subject, it is subjectified; similarly, when an element of the subject is removed from the subject itself and is treated as an object of experience, it is objectified.

Your conceptualizations are objects that can vary in their jectivity. They are the products of something that you are doing. When you forget about that, and “absorb” them into your sense of self, then they are subjective. If something in one of your conceptualizations is so absorbed that you don’t realize that it is just something that you are thinking about, then it is subjective. When you remember that they are objects that you can volitionally cognize, and that you can refer to them and their contents, then they get some perceptual attention as items that are not part of you as a subject, and they are treated more objectively.

The point is that your conceptualizations are like sunglasses, in that they (and their components) can shift in their jectivity.

Now consider the conceptualization of the ground (G), which consists of S, L, and their contextual circumstances. G helps to provide mutual mental contact. It acts as a communal reference anchor point, allowing Ps to meaningfully use words like “us,” “this,” and “there,” all to establish contact with the same intended referents. All expressions that invoke G objectify its components to some degree; that is to say, you can’t say something like “that nearby pig” without bringing some amount of perceptual attention to yourself as a point of reference from which to locate the pig. So those sorts of expressions also erode the objective scene.

In an earlier example, we portrayed the imperative [STOP] by diagramming part of G overlapping the OS; in specific, L is portrayed as an element of G on which the imperative mood has trained the perceptual spotlight in the OS.

So, if S and L are conversing about themselves as part of G, then they have objectified themselves; however, if they are talking about material that is not part of G, then they are taking turns acting more like full perceptual subjects, with their focus of attention on something that is away from them.

And with that, you are now ready to move on to a discussion of Communication and Sensory Lifestyles.